Quality in Health Care, 10 (Supp 2), ii59-ii63. PMID: 11700381

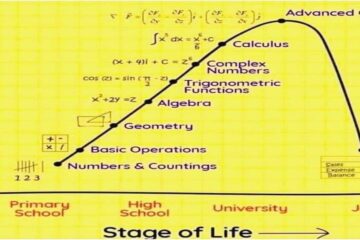

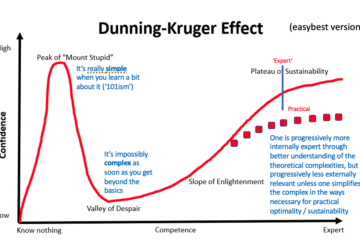

Most references to “leadership” and “learning” as sources of quality improvement in medical care reflect an implicit commitment to the decision technology of “clinical judgement”. All attempts to sustain this waning decision technology by clinical guidelines, care pathways, “evidence based practice”, problem based curricula, and other stratagems only increase the gap between what is expected of doctors in today’s clinical situation and what is humanly possible, hence the morale, stress, and health problems they are increasingly experiencing. Clinical guidance programmes based on decision analysis represent the coming decision technology, and proactive adaptation will produce independent doctors who can deliver excellent evidence based and preference driven care while concentrating on the human aspects of the therapeutic relation, having been relieved of the unbearable burdens of knowledge and information processing currently laid on them.

History is full of examples of the incumbents of dominant technologies preferring to die than to adapt, and medicine needs both learning and leadership if it is to avoid repeating this mistake… the handloom weavers and many of those who employed them expired with the arrival of the weaving machine; the stage coach operators died out with the arrival of the train and bus; and the hot metal printers of Fleet Street, who held out against computer typesetting for many years (in collaboration with a cartel of employers not willing to bite the bullet),

Clinical guidance programmes (CGP) based on decision analysis oVer the decision technology that can enable independent practitioners to deliver evidence based, preference driven, cost effective care, and have a life.Leadership and learning should be directed to proactive adaptation to this coming technology, not attempts to sustain the waning one.

Can there be any serious doubt that the complex modelling and systematic incorporation of evidence, relating to both the individual patient’s clinical condition and their personal preferences over health states, give a CGP a priori claims to be a superior Decision Technology? … Is there any serious doubt that evaluation of these claims cannot properly be undertaken if clinical judgement is taken as the gold standard DT and departure from it is, by definition, penalised? It seems obvious that comparative evaluation of DTs should be carried out on a level playing field which does not privilege one of them, effectively making it judge and jury in its own case.

As in the rail industry and social work, it has therefore required major accidents or scandals (like the Bristol paediatric heart surgery case) to result in anything but a cursory look at the decision making processes of clinicians and the institutions in which they work. Even then, the diagnosis is fudged in the resulting enquiry because these are not truly organisational problems which can be solved by “better communication”, “better multi-agency cooperation”, “better error reporting”, introducing “whistle blowing systems”, or any of the other diversionary offerings from those who cannot accept that it is the quality of the reasoning, judgement, and decision making of human beings in general that is at the root of the problems. These problems will only be addressed successfully and permanently when it is accepted that decision making is an activity in relation to which relevant analytical skills exist; that these analytical skills need to be recognised, taught, and monitored equally as thoroughly as any other skills; and that supportive programmes and systems are essential to enable people to deliver the full benefits that can flow from more analysis based decision making.